Pte. Sefton Inglis Stewart - son of James and Margaret Stewart, of Richmond, Ontario, Canada.

Sefton Inglis Stewart was born April 11, 1898 to parents James Stewart and Margaret Clarke (Mclean) Stewart of Richmond, Ontario, Canada. His older sister was Clystal Clarke, and surviving younger siblings were George McLean, Evyleen May, Ivy Ireen, and Norma Leafa. Sefton was a high school student and enlisted with the 77th Overseas Battalion, Canadian Expeditionary Force March 21, 1916 at the age of 17. He was six feet tall, had blue eyes, and brown hair. Sefton loved his family, music, horses, and was of the Presbyterian faith. This banjo ukulele was one of Pte. Sefton Stewart’s prized possessions.

According to the Stewart Family, Sefton attended the performance of a Canadian Forces band visiting Richmond, Ontario and was so moved by the sound of the band that he enlisted with the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF). Although Sefton was underage at the time, his parents believed he would return to the recruitment office when he turned 18, so they supported his early enlistment.

Before Sefton departed for training the Stewart family hosted a going away party at their home. This home still stands on Perth Street, in the village of Richmond, Ontario (Stewart House: http://www.richmondheritage.ca/index.php/the-stewarthartin-house/).

Sefton Stewart with Richmond friends. From left to right: Muriel (Hemphill) Stewart, Sefton Stewart, Gertie (Mills) Moore. Photo was taken on the occasion of Sefton’s going away celebration.

Clystal (Clissie) Clark Stewart, older sister of Sefton Stewart, photographed at Sefton’s going away celebration.

Friend Lila Graham (left) and Margaret Stewart (right) taken at Sefton Stewart’s going away celebration.

Left to right: Sefton Stewart, friend Margaret Branley, and George Stewart. The photo was taken in front of Clystal Stewrt’s home, 213 Gloucester St, Ottawa, Ontario. Sefton was leaving for service with the C.E.F.

Journey to Bramshott Military Camp

In June, 1916 Pte Stewart boarded a train destined for Moncton, New Brunswick and he started writing letters home. Without knowing it, Sefton was recording history and preserving his Great War story with each letter and postcard. A large collection of his letters were diligently cared for by the Stewart family and donated to the Goulbourn Museum collections. As part of an exhibition titled With Love to All, the preserved letters are available to read online https://www.withlovetoall.ca/letters

The first letter in this collection, written to Sefton’s brother George, describes the journey to Moncton, New Brunswick and what wonders were observed through the windows of the train car.

“Dear Brother,

We are getting along fine, but are running slow will reach Halifax about [Monday] noon The country is very rough and thickly wooded but there is certainly some great sights. This line crossed the St. Lawrence and runs along side of it for quite aways. We saw some of the Thousand Islands. This evening there was a big moose standing with his head up in the air along side the track...

It started to rain this morning and has been raining all day, which will go very hard on the farmers, the crops are not any more advanced than around [Richmond] We have passed a few [fruit] orchards, and gone through mountains. The car is is rocking a lot making hard to write, We have already moved our watches on a hour, passed through New Castle wasn't that where Grampa lived It is now about eleven o'clock am getting sleepy intend to post this at [Moncton] if I see anybody After we sail you needn't expect any mail for over a couple of weeks because they say they hold the mail

Will write at Halifax. Best Love Sefton.”

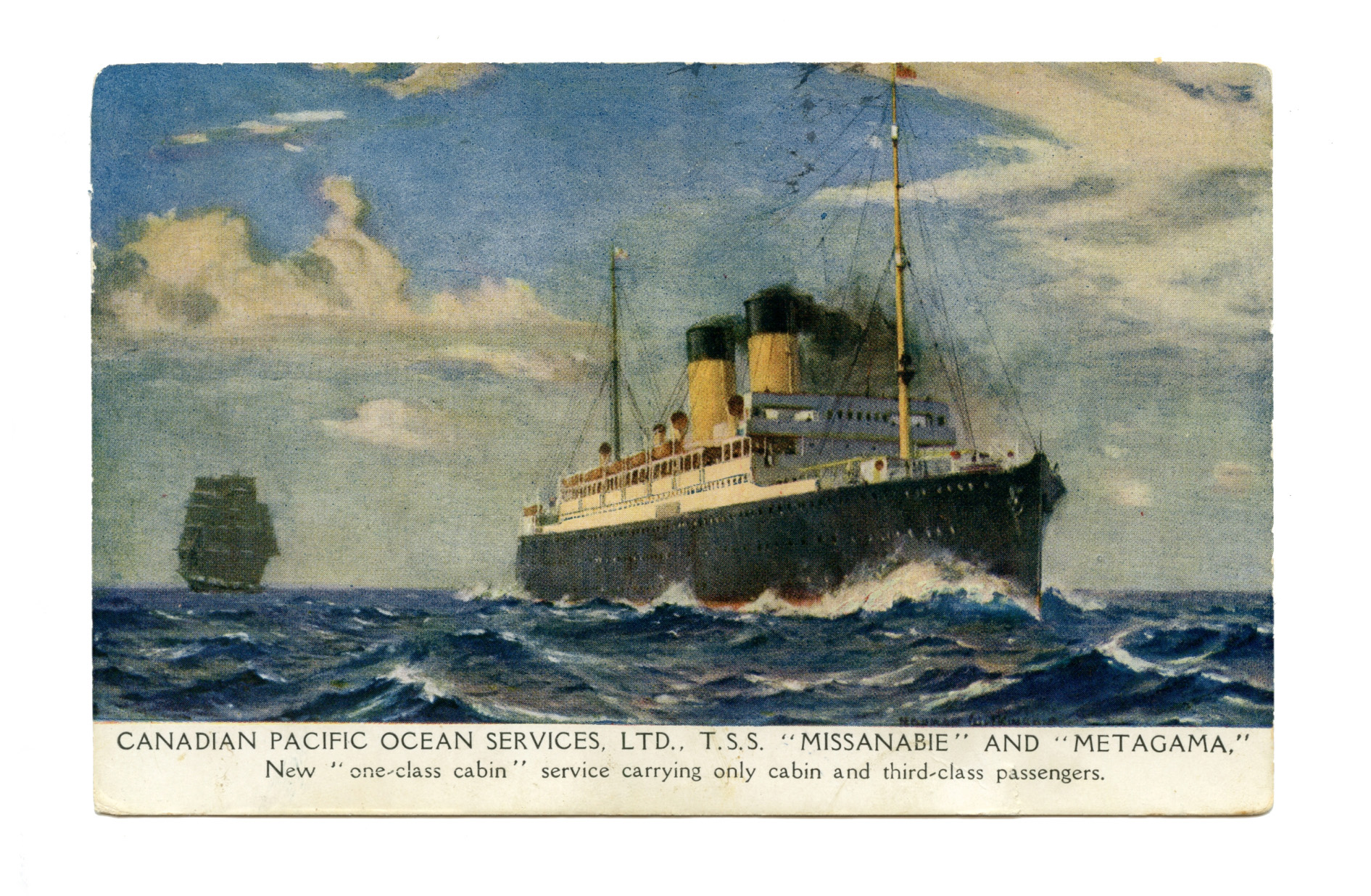

The next leg of Pte. Stewart’s journey was aboard the R.M.S. Missinabie destined for Liverpool, United Kingdom. Before leaving Canada Sefton sent his mother a post card bearing the image of the Missinabie.

“June 19th

Dear Mother

arrived here 11a.m. this is the picture of our boat. We didn’t see much of [Halifax] yet. Our other train hasn’t arrived but is expected soon. Everything seems strange but will get used to it.

Best. Love Sefton.”

The Missinabie and passengers arrived in Liverpool on June 28, 1916. The 77th Overseas Battalion was moved to Bramshott Military Camp where Pte Stewart penned a letter home.

“Dear Mother: -

How is everybody as for me I am quite well there are so many things to tell I don’t know what to tell… We had a very good trip, the weather being fine, except the first two days which were foggy. A great many were sick, Sid and Arthur were sick for half a day, but we were all dizzy at first. Left Halifax Tues. morning, arrived in Eng. Thurs 28th. Our ship, the Missanabie, Empress of Britain and the Drake a man-of-war sailed together saw quite a few ships, the Drake guarded them off to find their nationality, the water was very calm, so we saw a lot of large fish...

From Ottawa to [Halifax] there are some fine sights but is also a awful lot of bush. Went straight from train to ship therefore didn’t see much of [Halifax] but it doesn’t seem much of a place. Came into Liverpool Harbour [Thursday] night, it is a very large harbour being crowded with ships. From Liverpool to Bramshott Camp it is a bushy country divided up here and there with farms cultivated mostly by women. Stopped off in [Birmingham] Station which is a very busy place. got off at Liphoule Station marched from there to Bramshott Camp which is about two miles, this camp is so large you would easily get lost, there being about 40,000 troops stationed here… We are crowded in about fifteen in each tent, making it very hard to move around, the [accommodations] are yet poor but are getting things fix up as soon as possible, the first few days we had to march a mile + a half for dinner. Each Battalion has to fix up their own necessities, as there are Battalions coming in every few days keeping the transport wagons busy… fine roads all through the country, in the cities the streets are very narrow and buildings very low. On the 1st July there was an inspection of all these troops by the king at [Hindhead] eight miles from our camp. A. [Company] of the 77 went as a guard being the first time to see the king, it was some thing wonderful to see such a gathering of troops, there was a lot of fine horses in the artillery. It took them all afternoon to move off the grounds [Battalion] After [Battalion]. The drill is mostly with packs on, and a great many men fell out, that is of the Battalions that were inspected. They drill every day except Sunday and often they drill Sunday, as yet I don’t know whether the 77th will or not. The second day we were here there was an inspection by Lord Brooks Commander of this Camp a lot of the Battalions were divided, but we haven’t been yet. On ship we only a little physical drill in the mornings, on our ship there was 18,000 soldiers, a person never would imagine all the work + machinery there is about a ship. There was four sittings each meal there being accommodations for 4500 each sitting. The weather is very changeable raining frequently, our first night in camp it rained all night, we are surrounded by villages two and three miles away, there are some deep valleys giving a fine view of the country. The north coast of Ireland was our first sight of land which we were all anxious to see, the rocky coast is all divided off in small patches the grass is very green. When we came into the dangerous zone we were met by 3 torpedo destroyers a long low little boat, but has very high speed, these stopped with us until we reach England. (these belonged to Britain)...

I guess I will write all afternoon as it is our only time, but will have to take in some of the sports which are going on, must write to Clystal. Canadian mail goes Mon. + Thurs.

Best love to all

Sefton

Pte. Sefton Stewart

77 Battalion

A Co. No 1 Platoon

Bramshott Camp.

C/O. Army Post Office London England.”

Pte Stewart along with other members of the 77th were taken on strength by the 73rd Battalion, Canadian Infantry, Royal Highlanders. Sefton wrote home to share the news.

“...we are now transferred into the 73 Battalion these are Highlanders, so we will have to put on the kilts. This is looked upon as the best [Battalion] that ever left Canada, all the 77 is being broken up too…”

Pte Sefton Stewart wearing the uniform of the 73rd Battalion.

At this point Sefton is separated from some of his hometown friends, in particular he writes about Arthur Lewis, “ We were sorry for Arthur, but we tried our best to get him with us…”. Sefton had enlisted around the same time as a number of friends from Richmond. Before leaving Canada they sat for a portrait together. Unfortunately before the Armistice was reached on 11 November 1918, three of the five friends would be killed in action serving with the Canadian Expeditionary Force.

Left to Right: Earl Dobson, Irvin Brown, Arthur Lewis, Sefton Stewart. Front Centre: Sydney Sullivan.

73rd Battalion

In August 1916 the 73rd Battalion was moved from Bramshott Camp to France and then Belgium. In a letter home in August, 1916, Sefton describes the situation in France and Belgium, acknowledges a cake he received from home, and asks his mother for help getting money after not receiving pay for one month.

“Dear Mother --

Just a few lines to let you know we are all well, hoping you are all the same… Stopped in France a few days, and then came right through to Belgium. France + [Belgium] are more like Canada than England, the crops being splendid.

You already know that they are very particular about any information given, making it hard what to say. The airships are continually flying over our heads, it is certainly great to see how they can handle them, quite often shells are to be seen bursting all around one…

It is said the Germans are very done out on this front, but are causing quite an [excitement] yet… I forgot to tell in my other letter of receiving a cake when in Bramshott, but didn't know whether it was from you or Clystal, anyway the box was all broken up together with the cake, but we certainly enjoyed it. One thing missing most now is money not being paid for about a month + and only getting one franc or twenty cents per day…

The Germans seem to know every move, having up on a sign board "Welcome 73rd". The British artillery seems to be landing over the shells much thicker than the Germans…

One companion we always have is our gas helmet, in fact we carry two all the time…

Best Love To All

Sefton”

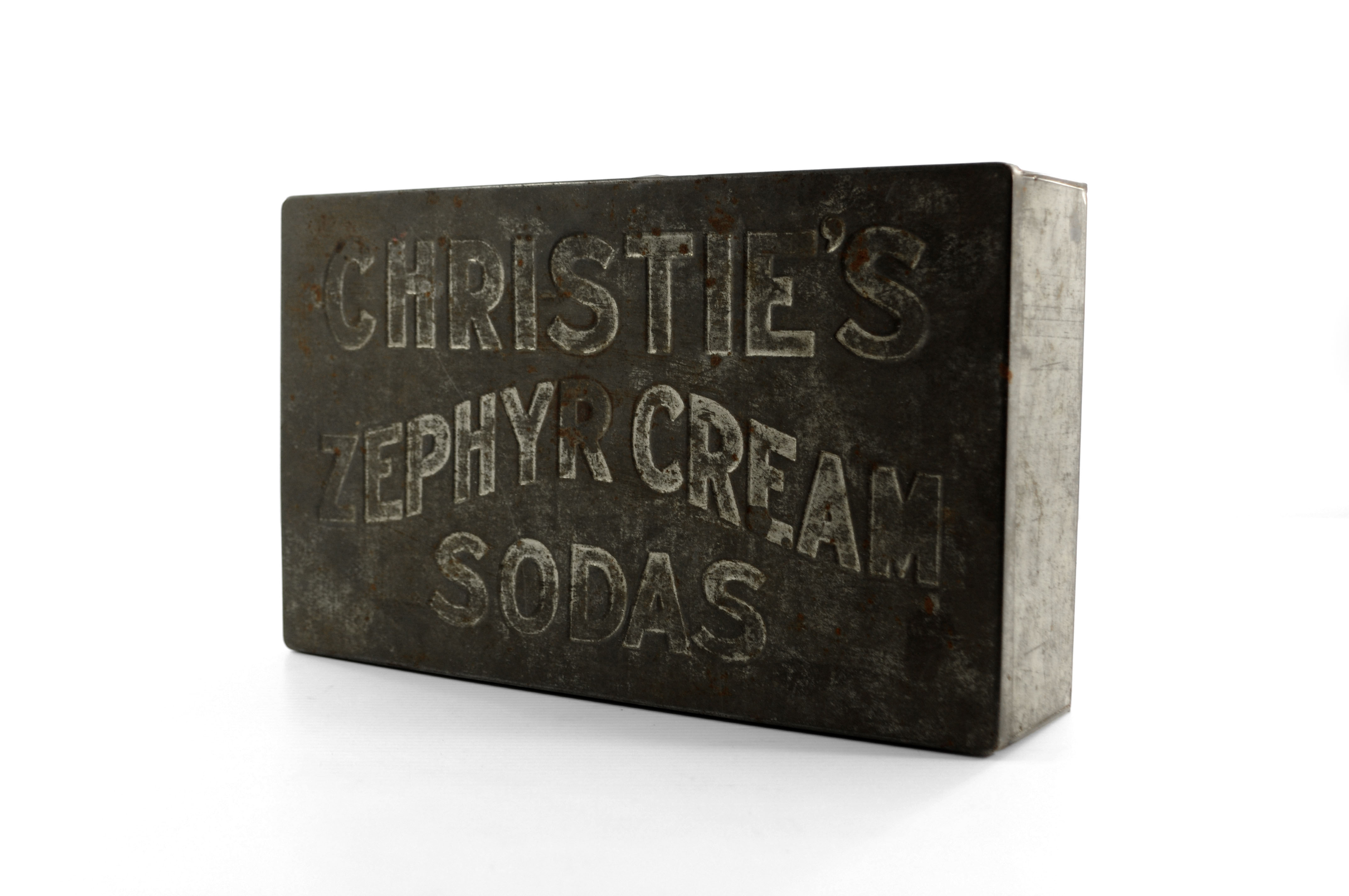

Metal box saved by Stewart family, similar boxes were sent overseas filled with items for Sefton.

In September Sefton writes home from “Some Where in France” and describes his experiences in the trenches. A portion of his letter has been physically cut away by the military censors.

“It is very hard to get a chance to write at present, we being in the trenches, the other day I sent a field post card to mother… Everything is going very good in the trenches at present, but the night we came in it was very wet, being mud up over our boots…

I am writing this in a dugout, the paper I got from another fellow who paid two francs and a half for it, or fifty cents. It is hard to give much news when not being able to tell where we are… We certainly do a lot of moving around, being here and there in a few days…

Today I am on guard at head quarters, looking after the traffic, and also being on the alert for gas. We have to carry [two] gas helmets together with a steel one which we wear all the time when in the trenches.

Sid and Ervie are transferred to C. [company] and are now separated from us, they are in the [battalion] bombers. will see them after coming out of the trenches, when the battalion will again unite together.

Some claims the war will be over shortly, but it is hard to tell.”

In October Sefton took an opportunity to sit for an updated portrait with friend Earl Dobson. The photograph shows the two men dressed in the 73rd Regiment’s highland uniform which included a tunic, kilt, and sporran. The two men are also wearing their “Brodie” helmets.

“Dear Mother:-

Just a few lines to let you know we are all well, hoping you are all the same… The other day we passed through a town where there was a photographer this being our first opportunity of getting any pictures taken, we accepted this chance. Earl & I got them taken together Ervie & Sid were not billeted near us, they are to be sent to us in a couple of weeks as we left our address, if they turn out any good will send them.”

In a letter home penned November 6th, 1916, Sefton describes the conditions in France. In subsequent letters, Sefton confirms his location and participation in the Battle of the Somme.

“... This is my first opportunity of writing for about two weeks, am out of the trenches now two days. The weather has been… wet and miserable for the last month + is most likely to continue. I only wish you saw us when returning from the trenches, mud up to the eyes, & wet to the skin, some of the bog holes you have to throw back your ears to get through them. In our last spell in the line we had a great many casualties as you will see in the papers, quite a few of them being slight wounds also a good many cases of trench feet which is sure a bad thing, some of the lads are not able to bear anything on their feet or legs. I suppose you have a very good idea of where we are, the most of the Canadians being on this front. The land we now occupy had formerly been in the hands of the Germans, so you have an idea what kind of a district we have to travel over. I don't think there is a [square foot] of land but what is turned over, no matter where you are, you are surrounded by ruins, of small villages & towns, it is too bad to see so many old fashioned churches all destroyed. In this ground, there is almost a underground world of German dug-outs, really there seems to be no end to the work they have put up in the construction of these. Had to stop this letter as you will plainly see in the difference in pencil, on having to fall in a… old parade. I only wish you saw the position I am in while trying to write, bent over on my knees receiving all the light possible from a piece of candle. At present there is a beautiful display of our old shack, some have fallen asleep, others eating a bite, the remainder, have their shirts off reading the news, which is very often interesting…”

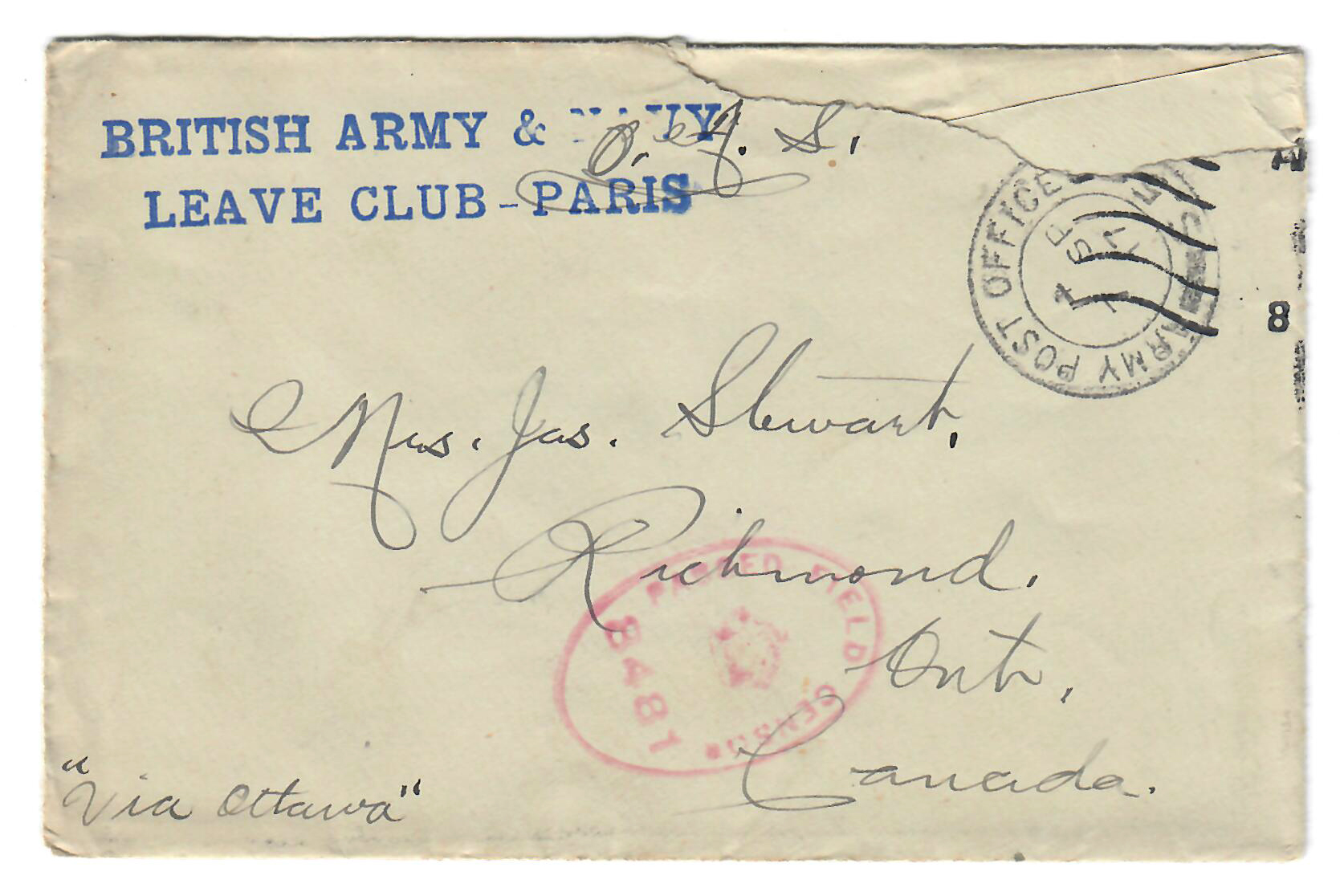

In December, with over a month without news, think of the relief and excitement his family would have felt the day this letter arrived. Finally, news from the front!

Sefton addresses this directly. “I suppose you people be very anxious when not receiving mail regularly, well there is no need of worrying because you know the circumstances here for writing + no news is always good news, If anything should happen [to] any of us you would be notified shortly.”

Sefton writes about the Somme, “...I guess you knew where we were down on the Somme, the [Richmond] lads are all very lucky coming from there safely, as you will already have a idea of it from the papers…” However, he does not elaborate. “…would like to tell you some of my experiences, but it is not allowed.”

Next Sefton drafted a four page letter to his brother George. Unable to reveal much, he does his best to paint a picture of the Battle of the Somme. “…I wish I could tell some of our experiences down on the Somme, it sure was some dive, lost a great many of our men...”

Christmas was two weeks away but for a soldier on the front, there’s not much time to celebrate. “Well I guess we have had our little Christmas holiday, being billeted in a little town for a few days, this is the rest all troops get after leaving the Somme.”

1917

Sefton’s first Christmas overseas was spent in the trenches. At his first opportunity on New Year’s Day 1917 Sefton wrote to his sister Clystal.

“Dear Clystal:

Am just out of the trenches, [haven't] written you for some time, did you get any of those [Christmas] gifts, they were small but would be a remembrance anyway, they may be a little late, but we did the best under the circumstances here.

Have received quite a bit of mail lately from both you + home together with the surrounding country, got a parcel from you yesterday containing almost everything, canned goods, nuts, candies, etc. On [Christmas] day which we spent in the trenches…

This is the first time we have been getting mail while in the line since leaving the Somme, things are not quite as rough here as the Somme, but it is sure wet + muddy, it rains here almost every day, + two or three times on Sunday, which is our only identification of the sabbath here.

On [Christmas] Day we got orders not to open fire at all, a few of us were out in a sap, that is a strong front in front of the trench one of the lads signalled over for some Fritzies to come over + we wouldn't open fire, had about half over when [an] officer saw us up trying to get them over + put us down, they went back, we would of taken them prisoners, as they would be only too glad to get taken uninjured, as the men themselves are pretty well fed up with it as well as the allies. When night came on, it was different all together, there was sure a lot of reception, of artillery [ramparts] + everything else, there was quite a few casualties in our company, only one being killed, it being poor Walter Bishop he comes from the other side of the Carp, he was picked off by a sniper, its a fright how many of the 77th lads have been wounded + killed, in the list of [casualties] in the paper they don't give the unit they belong to now…

I think we are to get something good for dinner today, on [Christmas] we had "bully beef stew", that is sure a great compound. By the time this reaches you it must be hard to make out, but you will have to excuse, as they have been fixing up my office.

With Love

Sefton.”

In February, 1917 the first member of the “Richmond Lads” was killed in action. Sefton writes home to share the sad news of his friend Sydney Sullivan’s death which occurred during a trench raid in the lead up to the Battle of Vimy Ridge.

“Dear Mother!

Am just out of the trenches, + have some very sad news to tell which I suppose you have already heard about, poor Sid was killed on Feb.4th while being engaged in a raid on Fritz’s trench, it certainly is hard news to break to you, as I know how the people of [Richmond] + surrounding country will feel over it, especially Miss Dorras who I am now going to write too.

The rest of our lads are safe, but there was quite a few casualties throughout the Ottawa Valley, whose names you will see in the casualty list…

Well poor Sid was wounded somewhere through the back + didn’t live long after receiving it, which was good not having to suffer much. Sid was always so contented + at home anywhere, he was sure a good little soldier of course he was anywhere he was put, as you all know that…

It is almost impossible to send any of his belongings home of course they are would be of little use at any rate. Ervie is sending his hat badge to home.

I am sure this will go hard on you people around [Richmond], as there is so much going on here + so used to such things, that we can scarcely realize that he is gone, + there is always so many lads all together.

I think we are now done on the front, + are going out for divisional rest, it was a kind of a dangerous position we held here, they have been making these raids all along the line as you will see in the papers. There is great talk of peace at present as I am sure the papers are full of it, heard today the States declared war on Germany, but is hard to say whether it is certain yet, if so I think it will bring the war to a close shortly…

The weather is now very cold, it being exceptional cold for France they say… Well Mother I expect to able to continue writing for a few days so I will write soon telling you a little more news. You don’t want to get uneasy when hearing any of these reports as you will always get direct word. Well poor Sid is out of all troubles now the only worry will be to his parents and friends. Ervie has been very lucky together with myself

With Love To All

Sefton.”

In March, 1917, the Battle of Vimy Ridge was weeks away and Sefton writes home describing the incredible amount of work being done to prepare.

“Dear Mother:

Just a few lines to let you know everything is OK…

We have been in the trenches for some time, I therefore have had [not] much chance of writing…

At present we are in the support line, there being 24 men in a small dug-out so you have a slight idea how hard it is to write. There is talk of us going out after a few days more in the front line, but I don't know whether we will get divisional rest, which we have been expecting for this long time.

While in this line we do working parties, you have no idea how much there is to be done in the line of bringing up ammunition, supplies + material needed for the repairing of trenches, dug-outs, + also for tunneling or mining…

There is now great talk of peace suppose you have seen by the papers about the great advancing which is going on all along the line, especially on the Somme, I hope all the reports are true, but a great many of these reports are exaggerated.”

Vimy Ridge, April 9-12, 1917

The Canadian Corp, fighting together for the first time, advanced on Vimy Ridge from April 9-12, 1917 capturing the Ridge from the German army. Vimy Ridge was the high ground of the Arras region, which the German army defended with trenches and barbed wire. Taking it was a challenging task. As the Canadian Corp prepared for the attack on April 9th, Pte Stewart along with thousands of Canadians dug tunnels and trenches, prepared supplies, and raided German trenches to learn more about the enemy. Many soldiers lost their lives while completing these tasks even in the months before the Battle of Vimy Ridge officially began.

On the morning of April 9th, 1917, Easter Monday, the four Canadian divisions were preparing for the attack on Vimy Ridge. The battlefield was badly scarred by years of fighting, filled with mud, trenches, shell craters, and mine explosions. The first wave of more than 15,000 Canadian soldiers began the morning attack weighed down with heavy equipment, facing wind-driven sleet and heavy machine gun fire.

It was an early start for Richmond’s Sefton Stewart, as the 73rd Battalion and its four companies of soldiers prepared for the day’s events. At 5:30 a.m. underground mines beneath Gunner and Kennedy Craters exploded marking the beginning of the assault. C Company led an advance to the German army’s front line, while Sefton and the members of A Company sheltered in tunnels, or ‘jumping off positions,’ ready for orders to support the strike. A Company joined as the second wave, attacking Gunner and Kennedy Crater and digging trenches to connect to the new Allied front line. Remarkably, the 73rd Battalion achieved this with light casualties and by the evening of April 9th they were basking in the success of the day.

Church bells rang throughout Canada as news of success at Vimy reached home. At Vimy, snowstorms continued as the Canadian Corps prepared for the second day of attacks. Pte Sefton Stewart, supported the 73rd Battalion’s occupation of Cluny, Clucas and Clutch Trench, which previously had been part of the German army’s front line. A and C Company’s efforts were rewarded with rest on the evening of the 10th. Sefton and soldiers of A Company moved to a dugout along with Headquarters staff for the night.

As dawn broke on April 11th it’s hard to say if Pte Stewart would have even recognized it was his 19th birthday. Sefton and the soldiers of the 73rd Battalion had been in the field for seven days now and were tired. He likely spent his birthday digging trenches, bringing up supplies, and patrolling the area to ensure German soldiers did not return.

The Canadian Corps continued to advance on the German army’s front line. Even though they had captured Hill 145 the morning before – the highest and most important feature of the whole Ridge – they needed to prevent the German army from strengthening their line.

Sefton wrote his next letter to his brother George, on April 20th, 1917 sharing news that the 73rd Battalion had been broken up and taken on strength by the 13th and 42nd Battalions. This letter was censored and only one page remains, leaving us to wonder if Sefton had shared any of his experience at Vimy Ridge with his brother George.

“Dear George:

How is everything going? I suppose you are busy going to school. You people will be sur- prised to hear of the 73rd. being broken up, just for what reason I don't know but I think is on account of Nova Scotia not being represented in any division, as a [Battalion] + of course they have sent a great many men. I guess Sir R. L. Borden had quite a bit to do in this.

The [Battalion] was given the choice of going either one of the sister battalions 42nd. or 13th. who are both highland battalions from Montreal, am now in the 13th. [Redacted] Brigade [Redacted] [Division] The wasn't many of the 73rd. to be broken up as we hadn't been many reinforcements lately.”

In May, 1917 Sefton suffered a shrapnel wound to his left hand. In a letter home he assures his mother of his health and asks for a little money to spend at the canteen.

“Dear Mother:-

Just a few lines to let you know everything is O.K. Got a slight wound on the left hand, not bad enough to make hospital, but had to be inoculated, therefore I was sent out of the line for a few days… I never be anxious for mail, as I know you people must often be, of course I always like to hear the local news, one thing I would appreciate now is a little money, as there are plenty of canteens around,. but every little article is a high price,...

The weather has certainly been very fine the last few weeks, hoping it continues, am in B. [company] 13th.

With Love To All Sefton”

The Battle for Hill 70

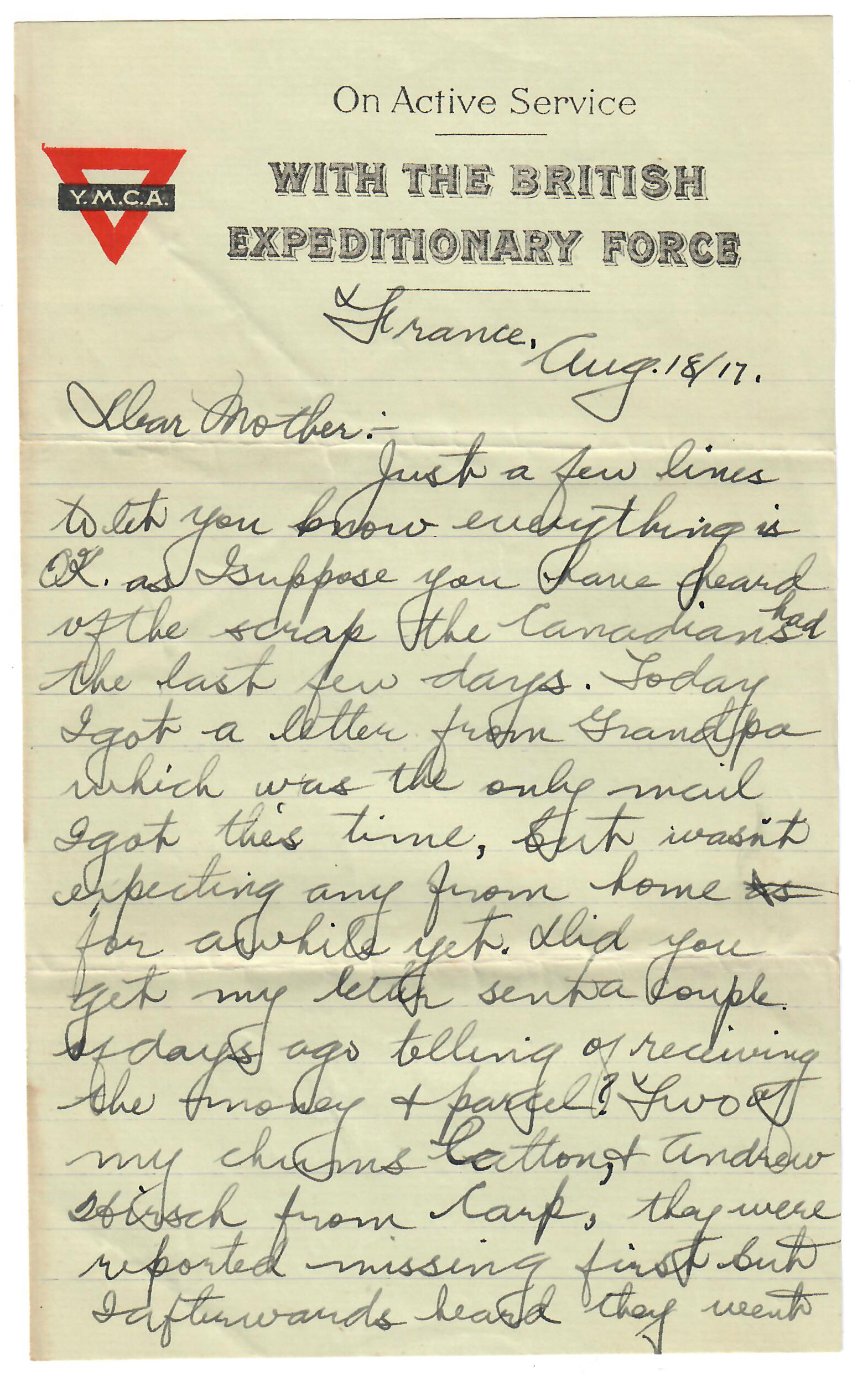

On August 12, 1917, Private Sefton Stewart penned a short letter to his mother while positioned “ half lying down receiving light from a candle.” In it, he expresses his appreciation for the constant support he is receiving from home.

Due to military censorship however, Sefton was unable to tell his family of the ongoing preparations for an offensive in which he was about to be a participant, now known as The Battle for Hill 70.

An often-overlooked battle in Canada’s history, the Battle for Hill 70 is an example of typical Canadian military prowess in the First World War. Named because it was 70 metres above sea level, this elevated strategic position was the high ground above the French city of Lens. In the summer of 1917, it was decided that the armies on the Western Front should capture Lens, to divert German reserves away from the ongoing battle of Passchendaele in the North. For the attack to be successful, the high ground had to be secured. The Canadian Corps, recently placed under the full command of Lieutenant General Arthur Currie, spent weeks methodically preparing to take Hill 70.

August 18th 1917 saw an exhausted Private Sefton Stewart writing a quick letter home to his mother to let everyone know he was okay. This letter is on the shorter side, and reflects the fatigue that Sefton would have been experiencing after participating in the Battle for Hill 70- an important Canadian victory.

Only days after Sefton sent his previous letter home, in the early morning of August 15th, the Canadians emerged from their trenches and launched an assault under the cover of thick smoke and poison gas. The enemy positions were taken but the soldiers spent the next three days defending against 21 determined German counterattacks fought with deadly mustard gas and flamethrowers.

By August 18th, the Canadians had secured the position. They had suffered 9,000 dead and wounded and inflicted 25,000 casualties on the Germans. Six Victoria Crosses, the highest British military honour, were awarded to Canadians for valour during this battle.

Sefton, fighting with the 13th Battalion, helped secure the north ridge of the hill in the first wave of the attack. The Battalion held their position against near constant enemy attacks and artillery barrages so bad that only carrier pigeons could be relied upon to send messages back to headquarters.

The 13th recorded a total of 35 killed, 34 missing, and 193 wounded. On the day they were relieved from the front, the day this letter was written, the paymaster made an extra effort to pay as many of the soldiers in the unit as possible before nightfall so they could buy luxuries. Perhaps Sefton used his pay for some paper and ink to write this letter home.

This letter also shows signs of censorship on the second page where some information has been cut directly out of the paper.

In September, 1917, Pte. Stewart was enjoying some much-deserved leave in Paris following the hard-won battle in August. Sefton was clearly having a great time in the city, stating “am now in Paris enjoying myself to the highest extent I tell you it is a fine city or “[French]” "tres bon" You can't imagine what it is like until visiting it.”

“Well mother you would never know there was a war on here, so we have forgotten all about it for the ten days. was going to cable for a little money but there was little satisfactory as some of the lads had been waiting ten & twelve days, however we are having a good time as we are… Excuse short letters, have seen so much, don't know what to write.

With Best Love To All.

Sefton.”

Christmas 1917

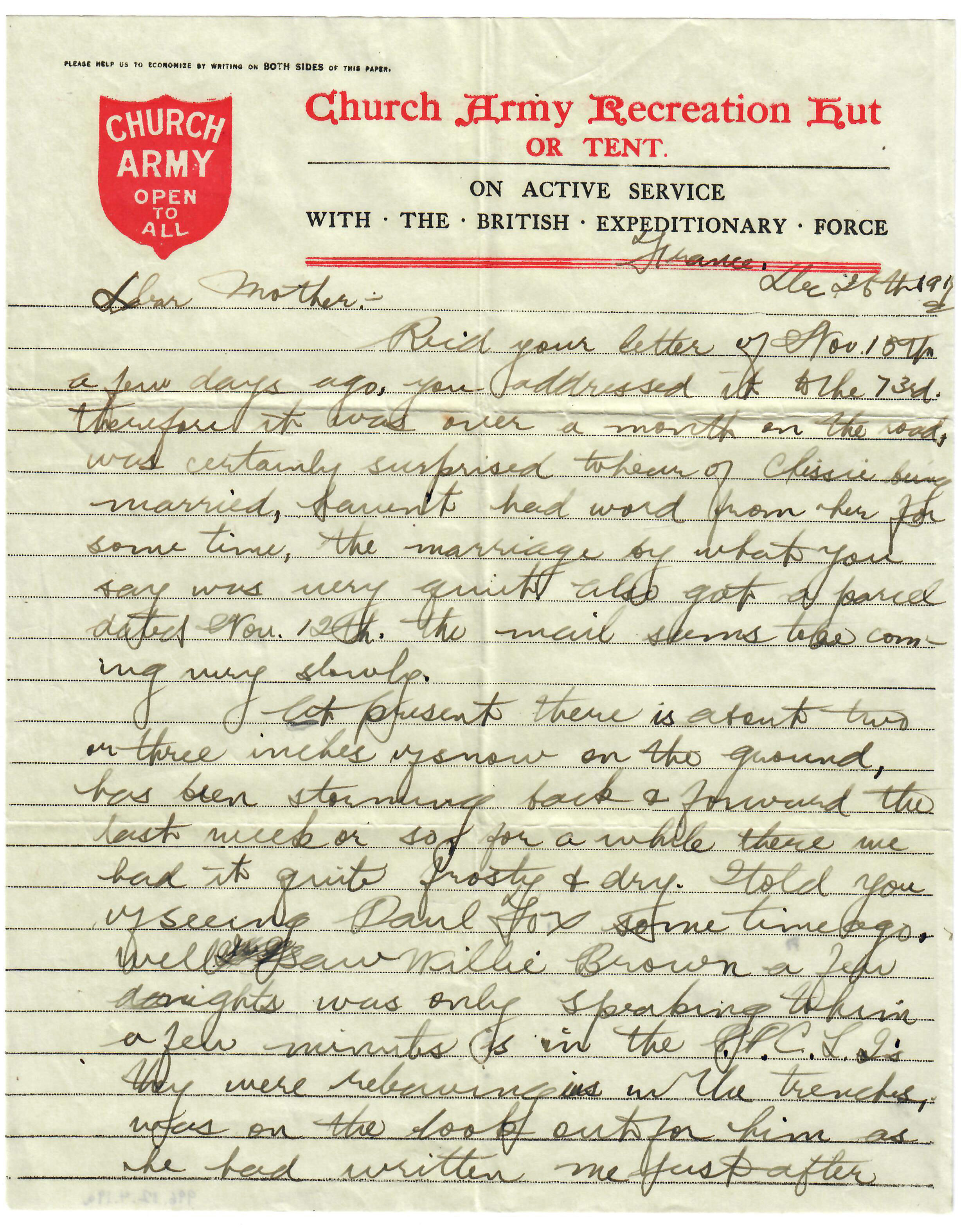

On a snowy December 26th 1917 somewhere in France, Sefton with his hands numb from the cold, wrote a letter home to his mother. He had just recently had a “very enjoyable [Christmas] under the circumstances” with a dinner consisting of “a little turkey good ham + potatoes of course the [Battalion] bought this themselves…”

We also learn about his older sister Clystal’s marriage to William Charles Mills, which had taken place on November 14, 1917. Sefton was surprised to hear about it, and we can only imagine what he must have felt to have missed such an important occasion.

Arras, France 1918

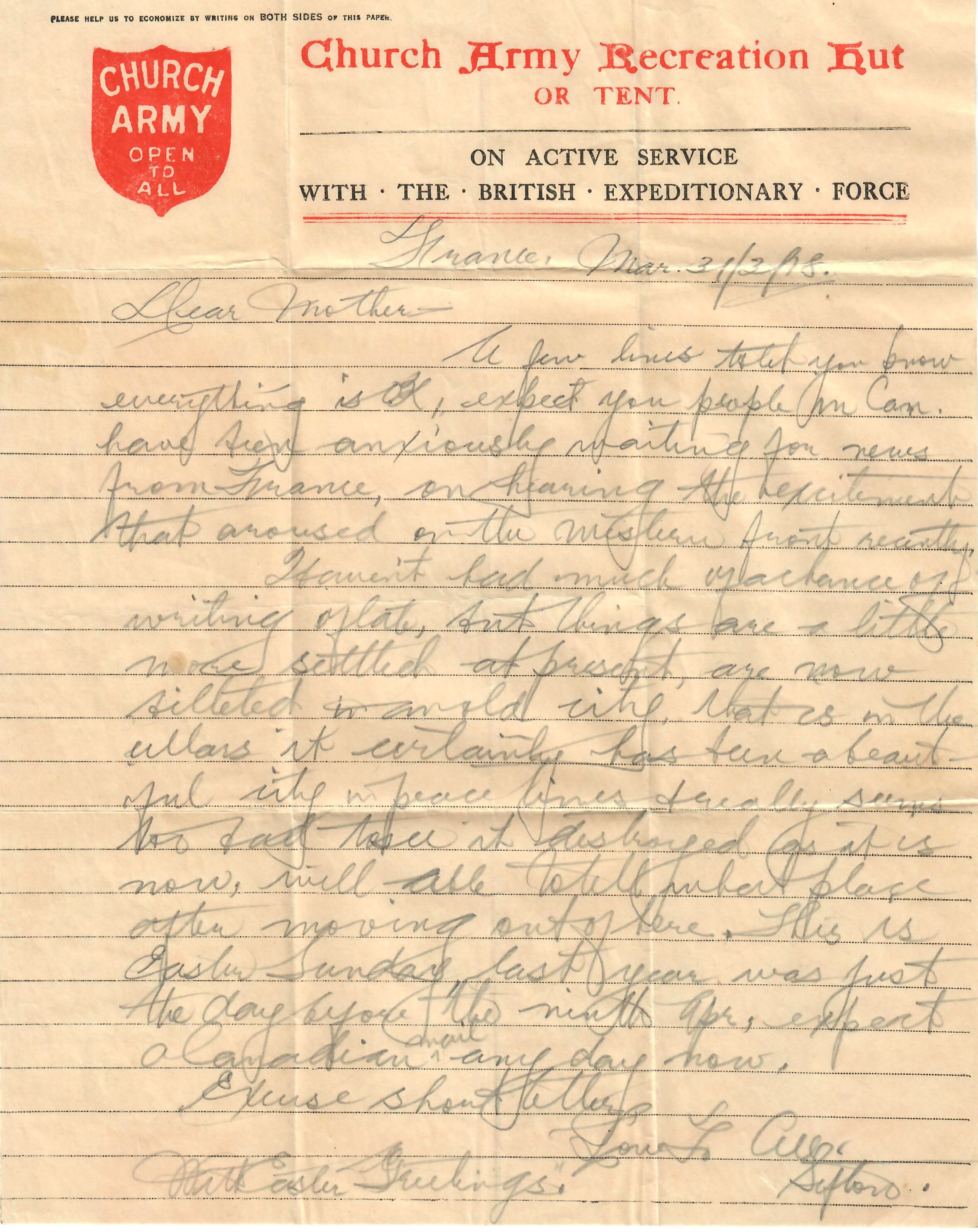

On March 31, 1918 Sefton Stewart managed to find some time to send this brief letter home. The young private, knowing that word of the ongoing German offensive would have reached Canada, sent this letter to reassure his family and give Easter greetings.

For operational security, he is unable to tell his family he is in Arras, France; however, he remarks,

“A few lines to let you know everything is O.K, expect you people in [Canada] have been anxiously waiting for news from France, on hearing the excitement that aroused on the western front recently. Haven't had much of a chance of writing of late, but things are a little more settled at present, are now billeted in an old city, that is in the [cellars] it certainly has been a beautiful city in peace times & really seems so sad to see it destroyed as it is now, will able to tell what place after moving out of here.”

On April 18, 1918 Pte Stewart managed to send this field card, or whizzbang, home. The term whizzbang originates from a type of artillery shell which, similar to these messages, would arrive unexpectedly and without forewarning.

Having spent the week of April 11, his 20th birthday, in combat on the frontline, the young man finally had this opportunity to let everyone back home know he was okay; however, the Allied Forces were still occupied in repelling the ongoing German offensive operations. It would be some time yet before Sefton would have the opportunity to pen a full letter home.

Finally, while we can't say for certain, it does appear Sefton underlined "first" in the line "Letter follows at first opportunity", to add extra emphasis to this notion.

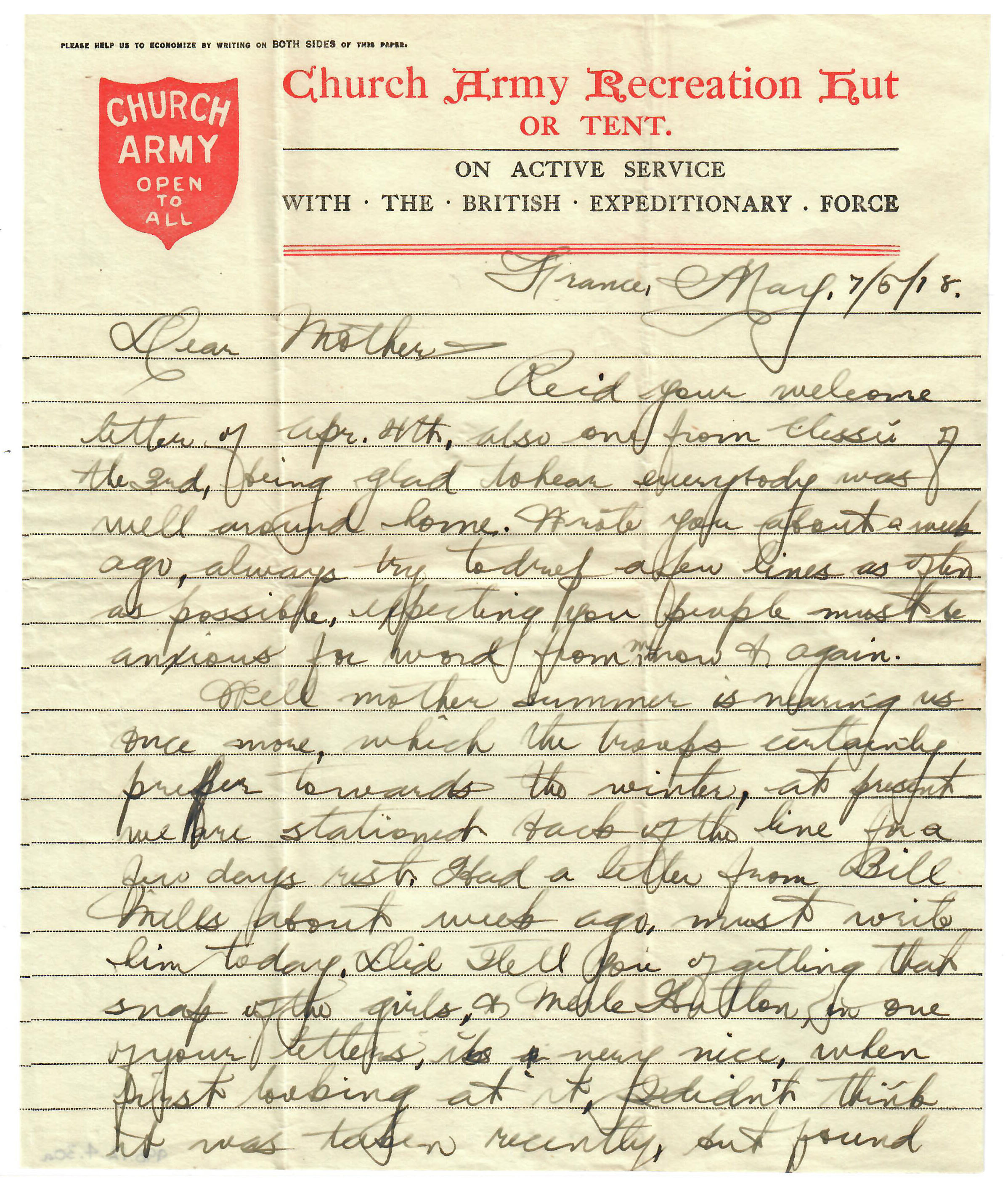

On May 7, 1918 Sefton wrote this letter home while given a few days of rest. In it, he talks about receiving letters from back in April, and the improving weather.

“Well mother summer is nearing us once more, which the troops certainly prefer towards the winter, at present we are stationed back of the line for a few days rest.”

Sefton also mentions his close friend A.H. Metcalfe, who we have heard mention of before in previous letters. Metcalfe would remain by Sefton’s side until the very end, and he will later play an important role in recording the story of Sefton Stewart.

In the War Diaries of the 13th Canadian Infantry Battalion, the entry for May 12, 1918 notes, "Nothing more restful could very well be imagined than this curiously peaceful Sunday."

In this rare moment of tranquility, Private Sefton Stewart took the opportunity to write this letter home. In addition to letting everyone know he is alright, he asks about the well being of his friend, Earl Dobson, who had returned home from the war months prior.

“Dear Mother,

Having an opportunity of writing thought I would drop a few lines to let you know everything is going O.K…

Suppose you people are now enjoying nice spring weather as for ourselves we can’t complain, the last few days being ideal weather for the time of year. Have been wondering lately if C. Dobson has arrived home yet, he sure is a lucky guy.”

On June 8, 1918 Sefton wrote this letter to his brother George. This letter cuts off at what seems to be a very poignant moment as Sefton offers his younger brother some advice.

It's unfortunate that we don’t know how this letter ended- whether it was so personal that those final pages were kept separate from the rest, whether they were censored or destroyed, or whether they were simply lost in the intervening century since they were written.

“Dear Brother >

…Well George am sure you found quite a change after leaving home, but [it's] really surprising how quick a person becomes acquainted eh! am sure mother must find it kind of lonesome at times, it being always lively when we were all at home, however we mustn't forget "there's a war on" at times there's no fear of not realizing it out here, the only thing gets on my mind is that mother + father must worry to a certain extent...

Mother told me in her letter you like the people of Russell very much. am sure its a very nice little town… take a tip from me George you don't want to travel too fast, for you are only a young lad yet. I can see my mistakes now…”

July 1st, 1918

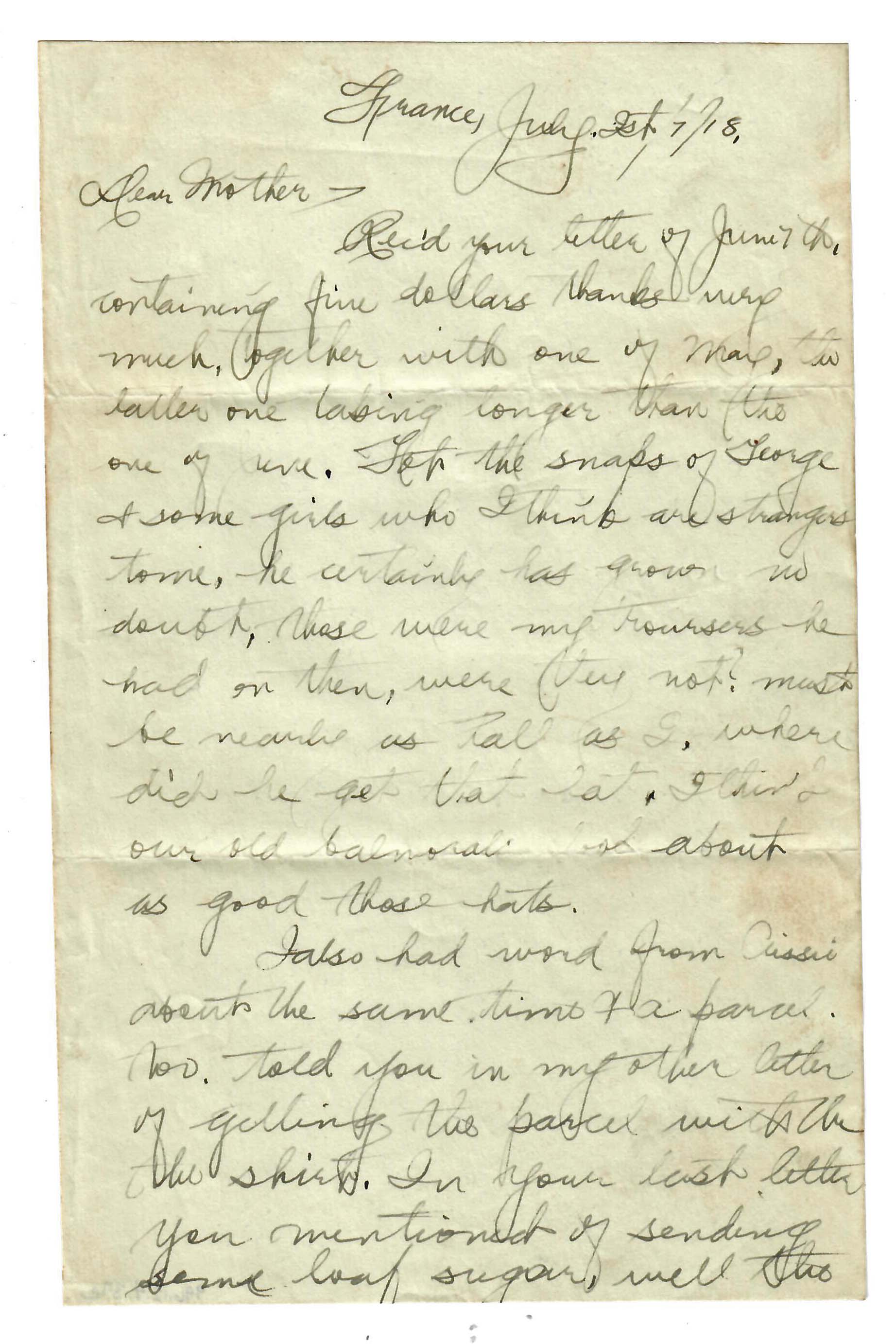

On July 1st, 1918, Sefton Stewart, would write this final letter home. Sefton expresses plans and dreams for the future talking about friends and family, and signing off with a postscript emphasising this fact.

While this is likely not the final letter Sefton ever wrote, it is a pivotal moment in our remembrance of the young man, and although his story does not end on this day, from this point forward the story of Sefton Stewart is told by others.

“Dear Mother,

[Received] your letter of June 7th, containing five dollars thanks very much, together with one of May the latter one taking longer than the one of June. Got the snaps of George + some girls who I think are strangers to me, he certainly has grown no doubt, those were my trousers he had on then, were they not? must be nearly as tall as I, where did he get that hat. I think our old balmoral look about as good as those hats.

I also had word from Clissie about the same time + a parcel too. told you in my other letter of getting the parcel with the shirt. In your last letter you mentioned of sending some loaf sugar, well the loose sugar is just as suitable, my friend Metcalfe often gets it in a little cotton sack. Did I tell you of seeing D. Reilly?, when on the march not long ago. haven’t seen any of the other [ Richmond] boys recently. By all accounts pork is a very high price, that was an exceptional price for those three pigs. Have so many letters to acknowledge that I hardly know who to write first. The [Canada] mail always comes in bunches here. We undoubtedly have been very lucky this summer so far, hope you are not worrying.

That must [have] been a nice trip to the Falls, made pretty good time I think. You people ought to get a car, would then be able to take the odd run down to Ottawa or the Falls without [losing] any time (over)

Had a letter from Agatha [indecipherable] Cauley not long ago, telling me that Rog. had joined up but had got two weeks leave to put in the crop, they are sure picking the young fellows up eh! how are the Eadies lads coming along? answered E. Dobson’s letter about a week ago.

Suppose you people are having warm weather just now, am writing this on the 30th June but it won’t leave until tomorrow which is Dominion Day in Canada am wondering if they are having any celebration around [Richmond] Say mother if you think of it when sending a parcel you might send a [dozen] razor blades as it is kind of hard to get them out here.

With Love to All.

Sefton.

P.S. did you give the [indecipherable] my [address] when sending that money? haven't been notified yet!

S.S.”

The Last 100 Days

In July 1918, the Allied Forces of the First World War began an offensive strategy that would push German forces out of France. As part of this, they planned an attack in the Amiens region of northern France to protect the vital Paris-Amiens railway. The attacking force was composed of the Canadian Expeditionary Force, the British Army, the French Army, the Australian Corps and others. Troops moved to the front lines at night to fool the enemy. False movements were made in daylight, amid decoy noise, dust and fake radio communications.

The 13th Battalion’s movement to the front line on the night of August 6th was not entirely uneventful. “The roads were jammed with traffic of all description and the roar of numerous exhausts was so loud that it seemed impossible the enemy could fail to hear it. Low flying aeroplanes were used in an attempt, apparently successful, to drown the noise, for the Germans gave no sign that it had reached them…” (Fetherstonhaugh, 249).

On August 7th, “fine weather proved a boon to the men, who lay around in shell holes and communication trenches, keeping all movement carefully concealed. No fires were permitted and a strong force of aeroplanes patrolled all day to prevent the enemy from observing the assembly. As two brigades were crowded into an area that would ordinarily accommodate one battalion, it was a literal fact that officers, in some cases, had to walk over the men while arranging dispositions” (Fetherstonhaugh, 249).

At dusk the 13th Battalion moved into their jumping off trenches reporting they were ready by 1.45 a.m. on the 8th of August. Throughout the night the German artillery was active, possibly suspecting that something was about to happen.

At exactly 4:20 a.m., 900 Allied guns opened fire and Pte Stewart, among members of the Canadian Corps, together with the Australians on their left, advanced on the German line. Visibility was poor on the battlefield with mist and smoke making it difficult to see more than 30 to 45 feet ahead. This made it very difficult for the tanks supporting the 13th to see where the infantry was having trouble.

In clearing Hangard Wood the 13th ran up against several machine guns, which caused serious trouble. Many soldiers showed bravery and skill during the fighting in Hangard Wood. The shortage of bombs required members of the 13th to outflank machine guns instead of smashing up their positions with bombs and grenades.

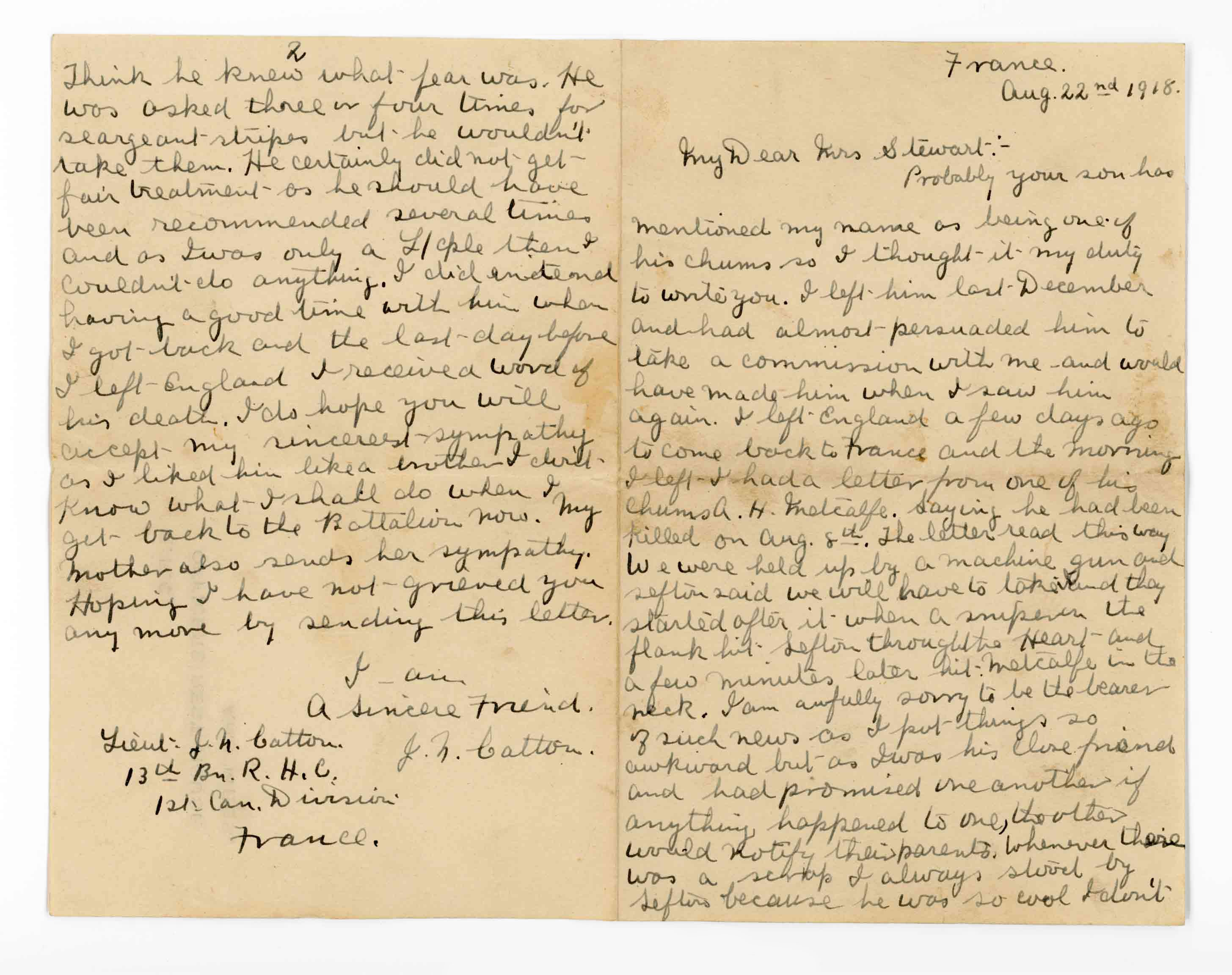

It is our understanding that it was a circumstance similar to this where Pte. Sefton Stewart was killed in action. From two letters penned to Sefton’s Mother by friends who had served alongside him, we learn more about Sefton’s final moments.

Westholme Aux. Hosp. Market Drayton, Salop, Eng.

Aug 21/18

Dear Mrs Stewart: I feel it my duty to inform you of the circumstances regarding your son Sefton’s death. For over a year he has been my best pal and we were constantly together. It came as a great shock to me as he was killed right beside me by a machine gun bullet. It went through his heart and he didn’t speak. I was wounded in the neck a couple of minutes later. I am sure he did not suffer any pain. I wish to extend my sincerest sympathy. I feel his loss greatly in fact I can hardly convince myself that he will not be there when I return to the [battalion] May I close again extending to you his Mother my sincerest sympathy I shall always consider Sefton the best pal I ever had.

Yours sincerely A H Metcalfe

France. Aug. 22nd 1918

My Dear Mrs Stewart-:- Probably your son has mentioned my name as being one of his chums so I thought it my duty to write you. I left him last December and had almost persuaded him to take a commission with me and would have made him when I saw him again. I left England a few days ago to come back to France and the morning I left I had a letter from one of his chums A. H. Metcalfe. Saying he had been killed on Aug. 8th. The letter read this way We were held up by a machine gun and Sefton said we will have to take it and they started after it when a sniper in the flank hit Sefton through the Heart and a few minutes later hit Metcalfe in the neck. I am awfully sorry to be the bearer of such news as I put things so awkward but as I was his close friend and had promised one another if anything happened to one, the other would notify their parents. Whenever there was a scrap I always stood by Sefton because he was so cool I don’t Think he knew what fear was… I did intend having a good time with him when I got back and the last day before I left England I received word of his death. I do hope you will accept my sincerest sympathy as I liked him as a brother I don’t Know what I shall do when I get back to the Battalion now. My mother also sends her sympathy. Hoping I have not grieved you any more by sending this letter.

I am a Sincere Friend. J. N. Catton Lieut.

It would be 10 days after August 8th before news reached the Stewart family in Richmond, Ontario. The telegram from Ottawa, dated August 19th 1918 reported, “Deeply regret inform you 145820 Pte Sefton Inglis Stewart infantry officially reported Killed in Action August 8th.”

August 8, 1918

August 8, 1918 is the solemn conclusion of Sefton Stewart’s story, one that has been preserved in the form of nearly 70 letters. Sefton’s words were his connection with home, limited in what he could share about his own experience, but always caring about those he loved and about his home. Invited into these personal conversations, we witnessed Sefton’s growth from a young student in 1916, to a wise young man offering his younger siblings advice from his position “Somewhere in France.”

Headstone of Private Sefton Inglis Stewart and wreath on the occasion of his internment. Killed in Action on August 8, 1918. Demuin British Cemetery.

August 8, 2023

On August 8, 2023, the Goulbourn Museum, Stewart family, and community recognized Private Sefton Stewart on the 105th anniversary of his death which occurred during the Battle of Amiens in 1918. Sefton was laid to rest with his comrades at the Demuin British Cemetery, located in Démuin, France.

A private wreath laying ceremony was held in Sefton's memory. A natural wreath with a portrait of Sefton was first placed on the Cross of Sacrifice before ultimately resting with Sefton at his grave.

“They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old:

Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn.

At the going down of the sun and in the morning

We will remember them.”

Laurence Binyon. For the Fallen

The Goulbourn Museum would like to offer our thanks and gratitude to the Stewart family for entrusting the Museum with their family history and for supporting the With Love to All project over the past three years.

Research and writing by Jonah Ellens, Stefan Hiratsuka, and Sarah Holla.