10 November 2022

RAF Remembrance - stories of the fallen

Ever wondered what RAF remembrance looks like? Join us as we examine how the Royal Air Force marks its fallen this remembrance season.

Blog cover image: SAC Ireland (RAF Photographer), UK MOD © Crown copyright 2021

RAF poppies and wreaths at the Garden of Remembrance, Westminster Abbey (Sgt Jim Wise RAF, UK MOD © Crown copyright 2021)

Why was the RAF formed?

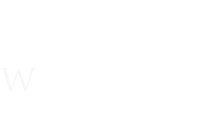

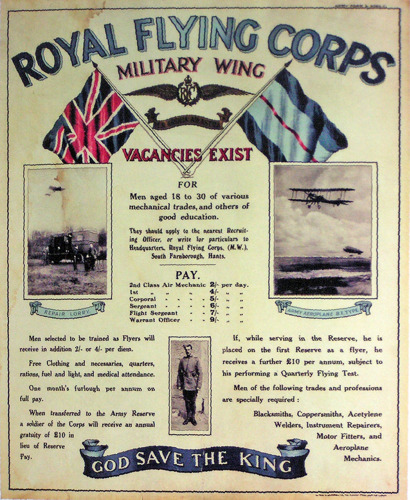

Image: A Royal Flying Corps recruitment poster from the Great War (Wikimedia Commons)

Image: A Royal Flying Corps recruitment poster from the Great War (Wikimedia Commons)

The Royal Air Force grew out of the Royal Flying Corps and Royal Navy Air Service on April 1st, 1918.

The Royal Flying Corps (RFC) was established in 1912 when British military figures began exploring the potential of aerial warfare. It literally added an entirely new dimension to fighting, which until then had been undertaken on land and sea.

The Royal Navy Air Service (RNAS) was the RFC’s naval counterpart.

Both organisations were run by the British Army and the Admiralty respectively. They formed the core of Britain’s early experiments with aerial warfare.

From the start of World War One up until the founding of the RAF, the RFC and RNAS fought in the skies all over the world. Pilots were considered dashing, courageous “Knights of the Air”. It’s true it did take extraordinary bravery to pilot what we would think of as relatively primitive warplanes. Aerial combat was in its infancy during the great war.

By the end of the war, over 6,000 men and women in the RFC, RNAS and the nascent RAF had been killed. Flying was dangerous enough by itself without having to dodge enemy fire in the sky and from the ground.

The importance of remembrance is such that we continue to recognise and commemorate these early aviation pioneers, these duellists of the sky. Not only did they give their lives to bring the Great War to a close, but their innovations and experiences also helped shape aviation as we know it today.

By the end of World War One, the RAF had around 300,000 personnel and over 20,000 Aircraft. Included in its ranks was the Women’s Royal Air Force until it was disbanded in 1920.

During the inter-war years, the RAF was scaled back. Part of its naval obligations was spun off into the Fleet Air Arm which would become one of the five fighting arms of the Royal Navy.

The RAF was gradually expanded in the 1930s as tensions rose over Europe. By 1939, build-up activity had accelerated with new aircraft and pilots being built and trained as fast as possible.

Image: Lancaster bombers of RAF Bomber Command. Bomber Command would take huge casualties during World War Two (© IWM TR 1156)

Image: Lancaster bombers of RAF Bomber Command. Bomber Command would take huge casualties during World War Two (© IWM TR 1156)

Summer, 1940 has gone down as the RAF’s finest hour. From June to September, the Battle of Britain raged over the skies of southern Europe as the RAF clashed with the Luftwaffe. The RAF came out on top, thanks to the efforts of its pilots as well as the hundreds and thousands of ground crew, radar operations, medical teams, and support staff keeping pilots airborne.

Bomber Command’s rate of attrition was astronomical during World War Two. While its role has attracted controversy in post-war discourse, there is no denying the danger Bomber Command aircrews faced.

Night after night, bomber crews flew dangerous sorites across occupied Europe, facing torrents of anti-aircraft fire and waves of enemy fighters. Some 57,000 or so airmen died in Bomber Command during the Second World War.

In total, including ground and aircrews, the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force, and related units like the RAF Regiment infantry divisions, the RAF took around 120,000 casualties during World War Two.

Included in their ranks are pilots from all over the Commonwealth, as well as from Allied and initially neutral nations. Canadians, Americans, Australians, Czechs, Poles, Free French and many more nationalities flew for the Royal Air Force during World War Two.

Remembrance Day gives us a chance to remember all those RAF personnel who made the ultimate sacrifice during the World Wars.

RAF Remembrance Day traditions

A member of the RAF Queen's Colour Guard stands sentinel at Cenotaph as part of 2021's Remembrance Sunday services (Sgt Donald C Todd, ©MoD Crown Copyright 2021)

RAF remembrance mirrors how the other armed forces commemorate their dead on Remembrance Day and Sunday.

Remembrance Day falls on the 11th of November each year.

The date has historical value. It was on the 11th of November 1918 that the Armistice was signed. This ceasefire between the Entente Powers of France and the British Empire and Imperial Germany marked the end of fighting on the Western Front, essentially ending the Great War.

Since 1919, we have continued to mark this occasion as Remembrance Day.

Its meaning has expanded since then. We don’t just commemorate and contemplate the sacrifice of the dead of World War One. Instead, Remembrance Day is a time to focus on all victims of all global conflicts.

One of Remembrance Day’s key traditions is the two-minute silence. This is a period where we stop what we’re doing and take a small amount of time to contemplate war dead around the world.

The two-minute silence is traditionally marked by a bugler sound The Last Post, a song that has since become emblematic of final service and sacrifice.

Remembrance Sunday is slightly different but runs on the same theme of commemoration.

The Sunday before November 11th is considered Remembrance Sunday unless the 11th itself falls on a Sunday that year.

The change was made during World War Two to ensure events and services could be organised properly during wartime. The change has also helped broaden the scope away from the Armistice and World War One.

So, what form does RAF Remembrance Day or Sunday take?

Usually, this means Royal Air Force personnel being involved in local and internal services and events. For instance, aircrew may join parades, attend church services close to nearby barracks, or hold private, RAF-only services on air force bases or in barracks.

For example, the RAF Queen’s Colour Squadron provided the honour guard at the feet of the Cenotaph at 2021’s Remembrance Sunday service.

The Royal Air Force may also put on fly-by events where historic and contemporary aircraft take to the skies in memoriam of those who flew them originally.

RAF Remembrance parade

Image: RAF troops on parade at Bury St. Edmunds, alongside British Army Soldiers (Cpl James Ledger RAF UK MOD © Crown copyright 2021)

Image: RAF troops on parade at Bury St. Edmunds, alongside British Army Soldiers (Cpl James Ledger RAF UK MOD © Crown copyright 2021)

As we touched on earlier, the RAF will be part of remembrance parades up and down the country.

The most viewed of these is the Cenotaph parade on Remembrance Sunday.

Senior RAF leaders as well as a small number of aircrew and staff will be present at the Cenotaph in central London.

The Cenotaph, meaning “empty tomb” in Greek is a large memorial made of stark white Portland stone. It is dedicated as a symbolic memorial to all casualties and victims of wars and conflicts around the world.

If the Cenotaph’s design looks familiar to you, you might be pleased to know it stemmed from the pen of Sir Edwin Lutyens. Lutyens was one of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission’s original principal architects and created some of our most iconic monuments, such as Thiepval in France.

Each Remembrance Sunday representatives of the armed forces come together to hold wreath-laying ceremonies and parades past the Cenotaph.

Other major parades take place in cities and towns throughout the UK. For example, in 2021, the RAF Regiment paraded through Edinburgh city centre, down the Royal Mile from Edinburgh Castle, climaxing with a wreath laying at the Stone of Remembrance.

At the Commission, we are involved in many different services and events come in November. To get an idea of what we do and how we do it, check out our remembrance roundup detailing 2021’s activity.

RAF Remembrance poppy

Image: Poppies are a powerful remembrance symbol (Unsplash)

Image: Poppies are a powerful remembrance symbol (Unsplash)

Go anywhere in the UK during November and you’ll see little red flowers pinned to many people’s chests. This is the poppy, one of the nation's strongest symbols of remembrance.

Why poppies? They were chosen as the flowers grow over what were once the killing fields of Flanders in Belgium.

The pretty red petals bloom each year, acting as a peaceful alternative to the mud, blood, and fire of yesteryear.

The poppy appeal was first organised in 1921 by the Royal British Legion. Proceeds from the sale of each poppy badge go towards supporting veterans, so if you’re in the UK in November and want to do some of your own commemorations, pick one up.

Poppies are incorporated into the remembrance of RAF personnel.

RAF stories of the fallen

Captain Albert Ball VC

I mage: Captain Albert Ball in front of the many aircraft he flew (Wikimedia Commons)

mage: Captain Albert Ball in front of the many aircraft he flew (Wikimedia Commons)

It seems almost inevitable that Albert Ball would become a pilot.

In his youth in Nottingham, UK, where he was born in 1896, Albert would while away the hours in a small shed on his family’s property, tinkering with engines and electrical equipment.

Speed thrilled Albert. He was a keen cyclist but that would satiate his need for velocity.

When he volunteered in 1914 following the outbreak of World War One, Albert was assigned to the Sherwood Foresters. He was desperate to get assigned to the North Midland Bicycle Division but even then, this wouldn’t be enough.

By 1915, Ball had started taking private flying lessons. He achieved his Royal Aero Club Certificate and requested a transfer to the Royal Flying Corps.

His early start in the RFC saw him piloting reconnaissance aircraft. While in the skies, Albert shocked his colleagues by throwing his craft around with complete gusto, displaying an absolute lack of fear.

Albert would also tweak and fettle his craft to ensure maximum performance.

Under the watchful eye of commanders like Kiwi Captain Cooper, the young Albert quickly graduated away from reconnaissance and become a fully-fledged fighter pilot of 56th Squadron RFC.

Behind the controls of aircraft like the temperamental French Nieuport fighters, Albert would become the highest-scoring British ace of World War One.

An ace is a fighter pilot with five or more confirmed kills. In his time as a fighter pilot, he shot down 43 enemy planes and even used rockets to take down an Imperial German balloon.

The Nieuport fighters Albert flew were known to be tricky planes to pilot and somewhat unpredictable. Albert seems to have had complete mastery of his craft. Coupled with his love for speed and incredible courage, Albert was able to dominate the skies for over two years. It’s thought his actions helped the RFC achieve aerial superiority during the Battle of the Somme.

On May 11th, 1917, Albert and 56th Squadron encountered enemy aircraft of the Luftstreitkräfte over Douai, France. A furious dogfight ensued: a deadly aerial dance of machine gun fire, tight manoeuvring, and rapid machine gun fire.

After fighting a running battle with visibility deteriorating, Albert’s plane tumbled from the sky alongside a German fighter piloted by Lothar von Richtofen, nephew of the feared Red Baron.

Albert was killed on impact while von Richtofen, whose plane also fell to earth, survived.

There has been some debate as to whether von Richtofen was responsible for shooting Albert down. Fighter aces were important propaganda tools as much as they were soldiers, so von Richthofen’s claims could simply be for appearances. We will probably never know the truth.

Albert was buried behind what were then enemy lines. His grave was discovered in later Allied pushes up the Western Front in the Great War’s closing stages. Instead of being transferred to CWGC purpose-built cemeteries, Albert’s father elected to let Albert lay where he was buried.

You can find Captain Albert Ball’s grave in Annoeullin Communal Cemetery.

For his considerable skill at arms and his huge tally of victories, Albert earned the Victoria Cross Distinguished Service Order and two bars, the Legion d’Honneur and Russian Order of St. George 4th Class.

First Officer Amy V. Johnson

Image: Amy V. Johnson (Wikimedia Commons)

Image: Amy V. Johnson (Wikimedia Commons)

We need to remember the sacrifices women made when considering RAF remembrance.

While women pilots were not allowed to serve in combat roles, a great deal many served in the Air Transport Auxiliary (ATA).

The ATA’s job was to ferry new, damaged, and repaired aircraft from factories, assembly plants, transatlantic delivery points, maintenance units, scrapyards, and active service squadrons and airfields.

One such pilot was First Officer Amy Johnson.

Amy Johnson had a remarkable pre-war flying career. As a sort of British equivalent to famous American aviator Amelia Earhart, Amy had broken many barriers for female pilots.

In 1930, Amy became the first women to fly solo from Britain to Australia aboard her plane Jason. Her list of firsts grew from there.

In 1931, with partner Jack Humphries, she became one of the first people to fly from Britain to Moscow in one day, covering the 1,760-mile distance in 21 hours.

Amy married Scottish pilot Jim Mollison in 1932. Shortly after, she beat her husband’s solo flying record from London to Cape Town. Together, the pair flew across the Atlantic to New York in 1933. In 1934, the Mollisons reached India from London in record time too.

Amy also beat her own London-Cape Town record in 1936.

With such a storied pre-war career, it’s little wonder Amy Johnson joined the ATA in 1940. Her husband Jim would serve in the Air Transport Auxiliary too during World War Two.

Unfortunately for Amy, it would not all be smooth flying during this time.

On 5th January 1941, Amy was ferrying an Airspeed Oxford aircraft from RAF Squires Gate in Prestwick, Scotland to RAF Kidlington near Oxford in Southern England.

Poor weather conditions affected the flight. Amy’s craft began to run low on fuel and she bailed out near the Thames Estuary near Herne Bay on the southeast coast.

A convoy of wartime vessels in the Thames Estuary spotted Johnson's parachute coming down and saw her alive in the water, calling for help.

Conditions were poor. The sea was heavy, the tide strong, with snow falling. The water and weather were bitterly cold. The captain of one of the vessels that spotted Amy, Lieutenant Commander Walter Fletcher of the HMS Haslemere, moved his ship in close to attempt a rescue.

Ropes were thrown to Johnson, but she was pulled under the ship and never seen again. Amy's watertight flying bag, her logbook and chequebook later washed up and were recovered near the crash site.

As no body was found, Amy is commemorated on the Runnymede Memorial.

Several witnesses believed there was a second body in the water. Fletcher dived in and swam out to the body, rested on it for a few minutes then let go. A lifeboat was dispatched to grab the Lt Cdr. When it reached Fletcher, he was unconscious, eventually dying in hospital several days later. For his attempted rescue ahead of his own personal safety, Fletcher was posthumously awarded the Albert Medal in May 1941.

Lieutenant Commander Walter Fletcher is buried at Gillingham (Woodlands) Cemetery in Kent.

Sergeant Leslie Francis Gilkes

Leslie Gilkes, right, with Sgt. Dickinson (© IWM PL 10348D )

The Royal Air Force was truly a multicultural force, representing servicemen and women of a multitude of ethnicities and nationalities.

Black airmen made a vital contribution and proved exemplary in air crews, particularly in Bomber Command. The “colour bar” restrictions on those “not of European descent” was lifted in 1939 and the Air Ministry announced in 1940 that it would accept black candidates from the colonies.

This prompted a major influx of volunteers entering the Royal Air Force from colonies in Africa and the Caribbean. Between 1940 and 1942, for example, around 3,000 volunteers from the West Indies enlisted in the RAF.

One of these was Sergeant Leslie Francis Gilkes.

Born in Siparia, Trinidad, Leslie volunteered in 1942. He did his initial flight training at the Royal Navy Air Station, Piarco in his native Trinidad, before setting off for England in August of that year. After being trained as an air gunner, Leslie was assigned to Bomber Command.

Black RAF servicemen were still subject to discrimination and racism while serving in Britain but the armed forces were not segregated. In warfare, lasting bonds are forged in the fires of combat and black crewmen like Leslie soon became incredibly close with their crewmates, regardless of race.

Leslie lived, flew, and fought with his compatriots who came from across the Empire. He was assigned to No.9 Squadron RAF and flew out of Bardney and Lincolnshire. His team’s Lancaster Bomber was crewed by three Scottish men while one of his fellow air gunners, Sergeant Dickinson, hailed from Canada.

As we spoke about earlier, Bomber Command had one of the highest rates of attrition in any branch of the armed services. Flying headlong over enemy territory, it was a lottery as to whether they’d ever see home again.

Exemplifying this was Leslie’s experience. His Lancaster was part of a flight of more than 700 aircraft taking part in the mass bombing of Hamburg as part of a series of raids called Operation Gomorrah.

After dropping their payload, Leslie and the crew headed for home. It would take several hours for aircraft to reach the drop zone and the same amount of time back. All the while, they had to dodge enemy flak, anti-aircraft fire and the predations of Luftwaffe fighters.

While flying over the North Sea, Leslie’s Lancaster was struck by enemy fire and crashed into the cold waves below. All seven of the aircraft’s crewmembers were tragically killed. While three of the bodies were washed ashore and are now buried in our Bergen-op-Zoom War Cemetery, Leslie’s body was never found.

He is commemorated on the Runnymede Memorial.

It’s important that we include black airmen like Leslie Gilkes in our RAF remembrance. They played a meaningful and all too often overlooked role in the air war of World War Two. It’s vital their sacrifice is not forgotten.

RAF memorials to visit

At the CWGC, we maintain several memorials dedicated to the commemoration of Royal Air Force personnel.

We like to think such memorials are a key part of RAF remembrance. Each memorial is dedicated to RAF personnel who died during the World Wars but have no known grave.

The nature of aerial warfare often precludes us from recovering the remains of the fallen. Pilots may have been shot down over enemy territory, crashed in remote areas, or gone missing or lost while flying over seas and oceans.

Our RAF memorials ensure these lost men and women are properly commemorated. They also act as a focal point for those looking to remember their loved ones and relatives that served in the Royal Air Force.

Runnymede Memorial

Runnymede Memorial sits in an area steeped in the echoes of the past. It was here in 1215 that King John and English nobleman inked Magna Carter, one of the most important documents in British history.

From its hilltop location, the Runnymede Memorial also overlooks Heathrow Airport, one of the busiest airports in the world. As planes take off and land nearby every day, it further connects Runnymede to Britain’s aviation history.

On Runnymede’s panels, you’ll find the names of 20,000 men and women who served in the RAF in World War Two but have no known grave. Those commemorated at Runnymede were lost on operations throughout the UK and North and Western Europe.

This is a multicultural, multiracial memorial. The Commonwealth is represented in full force here, with Canadian, Australian, British, Indian, New Zealand, and South African personnel all represented.

Runnymede casualties represent many branches of the RAF including the Woman’s Auxiliary Airforce, Air Transport Auxiliary, Bomber and Fighter Commands, Coastal Command, ground crew and more important aviation roles.

The memorial’s architecture was designed by Sir Edward Maufe with sculpture by Vernon Hill. The central square tower conjures up images of RAF command towers used at airfields during World War Two.

Further decorative engraved glass and painted ceilings, showcasing coats of arms of the commonwealth nations, were designed by John Hutton. A poem from Paul H Scott adorns the engraved glass of the central tower’s gallery window.

Engraved in the brickwork of Runnymede’s entrance you’ll find inscribed the Latin motto of the Royal Airforce: Per Arda Ad Astra. In English, that translates to “Through adversity to the stars”.

Arras Flying Services Memorial

The Arras Flying Services Memorial commemorates almost 1,000 air forces personnel from the Great War.

As such, the names on its numerous panels come from the Royal Air Force but also its precursors like the Royal Flying Corps and the Royal Navy Air Service. Also commemorated at Arras are men of the Australian Flying Corps.

Aerial combat over the Western Front was a deadly tussle from the outset. Innovations in aircraft design and pilot training meant attrition was high as one side gained an advantage over the other.

This could be seen in Bloody April, one of the worst months of the Great War for the Royal Flying Corps. As of April 1917, the RFC outnumbered its German counterpart, but the Imperial Germans had the advantage in pilot experience and aircraft.

Over the Somme, German fighters, including the feared “Red Baron” Richtofen cut a bloody swathe through the ranks of the RFC. In April 1917 alone, the Royal Flying Corps lost 250 aircraft and some 400 aircrew.

The Arras Flying Services Memorial commemorates these men as well as many others who lost their lives over the Western Front but with no known grave.

Singapore Memorial

The wings of the RAF and the Commonwealth air forces took them all over the world.

The Far East was an important theatre in World War Two. Here, British, Australian, Indian, New Zealand and local native forces clashed with the Imperial Japanese for control of places like Burma, Hong Kong, and Singapore.

Just over 24,000 missing service men and women from the Commonwealth are commemorated on the Singapore Memorial.

Look closely at the Memorial and you’ll see the architecture was inspired by aviation. Its panels sit below a top façade designed to invoke the swept-back wings of a World War Two fighter plane. A central tower juts skyward, resembling an aircraft’s rear fin.

In terms of RAF remembrance, nearly 3,000 or so casualties commemorated at Singapore served in the air force.

The RAF had a presence in British possessions in Asia since 1930 with the formation of Far East Command.

Initially, the lightweight, nimble, deadly Japanese Zeroes made short work of the obsolete and outdated aircraft the RAF could bring to bear against them. Once pilots were given updated aircraft, including American designs, the tide began to turn.

The air crew and pilots commemorated on the Singapore Memorial would have fought campaigns throughout the region, such as during the initial unsuccessful defences of Singapore and Hong Kong and the long slow grind to push the Japanese out of Burma.

We all too often overlook the efforts and sacrifices of the Commonwealth forces fighting in Asia during World War Two. This remembrance season, take some time to think about the men and women fighting the air war in the Far East.

Discover more stories OF RAF remembrance

At the CWGC we commemorate 1.7 million men and women from around the Commonwealth.

You can learn more about the men and women of the RAF we look after using our Find War Dead tool. Simply filter by service to learn more about these war dead.

You can also learn more about our sites around the world using our Find Memorials and Cemeteries tool.

What stories of Royal Air Force remembrance will you uncover?